4 Lab 4: Data subsetting

4.1 Objectives

In this lab, you will learn to:

- Pick rows based on their values

- Reorder rows based on their values

- Pick columns based on their names

- Combine multiple operations

4.2 Overview

A brief overview of the steps for this lab:

- Complete the steps in Getting Started below

- Read the next four sections which to learn how to subset of a dataset using the

diamondsdataset as an example - Read the entire Assignment section before beggining, then complete the requested assignment

- Submission your assignment

4.3 Getting Started

Your instructor has created a blank repository for you using GitHub Classroom.

Go to the course D2L page

Navigate to the Lab 4 module

Follow the link to claim your GitHub Classroom repository. After claiming your repository, copy its URL

-

Clone the repository to your machine:

In RStudio, create a New Project

Select the Version Control option, then GitHub

Paste the URL you copied, and press tab to autocomplete the directory name

Select a parent directory in which to place your new project folder, probably either

~or~/R.Click OK.

Once RStudio has started, double-check your Project Options as described in Lab 2. (set the options to not save .RData or .Rhistory files, and not auto-load them on startup)

-

Make your first commit:

In the Git tab, check the box next to the

*.Rprojfile to stage it for adding them the repositoryClick the “Commit” button

Enter a commit message such as “Create a new RStudio project”

Click Commit to submit the commit

-

Click Push to push the commit to GitHub

- If RStudio prompts you for credentials, follow the method you learned in Lab 2 (use your GitHub username and a Personal Access Token for the password)

-

Create two new R scripts:

diamonds-example.Rto use for the diamonds tutorial, which you can callpenguins-assignment.Rto use for the penguins assignment, which you can call

4.4 Introduction

Working with tabular data often requires manipulating the contents of the table. For example, you may want remove certain columns to make the table easier to read, or remove rows that do not match certain criteria before graphing.

You can manipulate tables easily with functions from the dplyr package, one of the core members of the tidyverse.

- Pick rows by their values using

filter() - Reorder rows using

arrange() - Pick columns by name using

select()

4.4.1 Prerequisites

In this lab you will use functions from the dplyr package. While you could load that package by itself, in this course you are encouraged to always load the entire tidyverse set of packages.

In addition to loading the dplyr package for you, loading the tidyverse package also lets you access the diamonds dataset from the ggplot2 package. This lab will use the diamonds dataset to show examples of filtering, arranging, and selecting.

Copy this code to your diamonds-example.R script and run it t load the tidyverse package:

#> ── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

#> ✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

#> ✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

#> ✔ ggplot2 3.5.0 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

#> ✔ lubridate 1.9.3 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

#> ✔ purrr 1.0.2

#> ── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

#> ✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

#> ✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

#> ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errors

4.4.2 diamonds

You will explore basic dplyr functions using the diamonds data frame, found in the ggplot package.

This data frame contains data on almost 54,000 diamonds, including price and other attributes.

First, take a look at diamonds by printing it in the console:

# print diamonds in the console

diamonds#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 55 326 3.95 3.98 2.43

#> 2 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 61 326 3.89 3.84 2.31

#> 3 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 65 327 4.05 4.07 2.31

#> 4 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 58 334 4.2 4.23 2.63

#> 5 0.31 Good J SI2 63.3 58 335 4.34 4.35 2.75

#> 6 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 57 336 3.94 3.96 2.48

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsFamiliarize yourself with the variables in the data frame by looking at the help page for diamonds:

help(diamonds) # method 1

??diamonds # method 2You can also get there by going to the Help tab (bottom right in RStudio) and typing diamonds in the search field (not the Find in Topic field).

If you get a message starting with “No documentation” or you search and do not find the diamonds data frame, it may be because you have not loaded the ggplot2 package yet, either directly or by loading the tidyverse package. Load it and try again.

The most important thing to note about the variables in the data frame right now are the variable names and their classes (the type of data they contain).

Note that when you printed diamonds in the console, the first line of the output said it was a tibble with 53,940 rows and 10 variables. The second row named the variables. The third row gave their data types: 6 numeric continuous variables labeled <dbl> , one numeric discrete variable labeled <int>, and three categorical ordinal variables labeled <ord>.

The data type labels need some explanation. Each data type represents a particular kind of data in R. These are similar to the categorical/numerical distinction you learn about in lecture, but there are more used in R, some for very specific purposes (e.g. the Date and POSIXt types).

The most common column data you will see in data frames are:

| Data type | Example | Description | 4-way clasification | Column header |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| logical | TRUE |

Logical values (true or false) | categorical nominal | lgl |

| integer | 1L |

Positive or negative whole number. The “L” is so R knows it’s not a double | numeric discrete | int |

| double | 1.5 |

Decimal numbers | numeric continuous | dbl |

| character | "A" |

Text; note that "1" is still a character data type because of the double quotes |

categorical nominal | chr |

| factor | factor("A") |

Text with an enumerated list of values; you can see possible values with levels()

|

categorical nominal | fct |

| ordered | ordered("A") |

Text with an enumerated list of values which have an inherent order; you can see possible values with levels()

|

categorical ordinal | ord |

| Date | Sys.Date() |

Date | numeric discrete | date |

| POSIXt | Sys.time() |

Date plus time | numeric continuous | dttm |

You can read more about data types in the Column data types vignette in the tibble package.

4.5 Filter rows with filter()

The filter() function allows you to take a table and pick rows to keep based on their values. The first argument is the name of the data frame. The other arguments are expressions that decide which rows to keep.

For example, to take the diamonds data frame and pick only diamonds with a weight of 2 or more carats, you could write:

filter(diamonds, carat > 2)#> # A tibble: 1,889 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2.06 Premium J I1 61.2 58 5203 8.1 8.07 4.95

#> 2 2.14 Fair J I1 69.4 57 5405 7.74 7.7 5.36

#> 3 2.15 Fair J I1 65.5 57 5430 8.01 7.95 5.23

#> 4 2.22 Fair J I1 66.7 56 5607 8.04 8.02 5.36

#> 5 2.01 Fair I I1 67.4 58 5696 7.71 7.64 5.17

#> 6 2.01 Fair I I1 55.9 64 5696 8.48 8.39 4.71

#> # ℹ 1,883 more rows4.5.1 Intermediate objects

When you run code to filter a data frame, R returns a new data frame.

If you want to use that new data frame for some further operation, you would need to save the result by assigning it a new name using the assignment operator <-

big_diamonds <- filter(diamonds, carat > 2)When you run this line of code, note that there is no output in the console. R generally does not produce any output when you use the assignment operator. If you want the new object to be printed in the console, you have to print it by running the name of the new object:

big_diamonds#> # A tibble: 1,889 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2.06 Premium J I1 61.2 58 5203 8.1 8.07 4.95

#> 2 2.14 Fair J I1 69.4 57 5405 7.74 7.7 5.36

#> 3 2.15 Fair J I1 65.5 57 5430 8.01 7.95 5.23

#> 4 2.22 Fair J I1 66.7 56 5607 8.04 8.02 5.36

#> 5 2.01 Fair I I1 67.4 58 5696 7.71 7.64 5.17

#> 6 2.01 Fair I I1 55.9 64 5696 8.48 8.39 4.71

#> # ℹ 1,883 more rowsNow, if you want to filter the big_diamonds object further, you can use it as the data object for another filter() function:

filter(big_diamonds, price > 15000)#> # A tibble: 1,037 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2.1 Premium I SI1 61.5 57 15007 8.25 8.21 5.06

#> 2 2.02 Premium G SI2 63 59 15014 8.05 7.95 5.03

#> 3 2.05 Very Good F SI2 61.9 56 15017 8.13 8.18 5.05

#> 4 2.48 Fair I SI2 56.7 66 15030 8.88 8.64 4.99

#> 5 2.8 Premium I SI2 61.1 59 15030 9.03 8.98 5.5

#> 6 2.19 Premium I SI2 60.8 60 15032 8.34 8.38 5.08

#> # ℹ 1,031 more rows4.5.2 Basic Operators

The > symbol is known as an “operator”. These are special characters you use to compare things in R. Some of the basic operators include >, >=, <, <=, == (equals), and != (not equals).

Note that the greater and less than operators can only be used on numerical and ordinal categorical variables, while == and != can be used with any type of variable.

There is one major difference between comparisons of numeric (integer and double) variables and character, factor, or ordered factor variables, and that is the use of the double quotes ".

Here is an example of using the == operator with the cut variable, an ordered factor data type:

filter(diamonds, cut == "Ideal")#> # A tibble: 21,551 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 55 326 3.95 3.98 2.43

#> 2 0.23 Ideal J VS1 62.8 56 340 3.93 3.9 2.46

#> 3 0.31 Ideal J SI2 62.2 54 344 4.35 4.37 2.71

#> 4 0.3 Ideal I SI2 62 54 348 4.31 4.34 2.68

#> 5 0.33 Ideal I SI2 61.8 55 403 4.49 4.51 2.78

#> 6 0.33 Ideal I SI2 61.2 56 403 4.49 4.5 2.75

#> # ℹ 21,545 more rowsNote that "Ideal" has double quotes around it. This is to tell R you want to find the literal text string “Ideal”. If you instead wrote cut == Ideal without the quotes, then R would look for an object named Ideal in your environment and, not finding any, would return an error.

Another common errors when you are starting out is to try to use = instead of ==. When you do that, you will get a helpful error message:

filter(diamonds, carat = 2)#> Error in `filter()`:

#> ! We detected a named input.

#> ℹ This usually means that you've used `=` instead of `==`.

#> ℹ Did you mean `carat == 2`?4.5.3 Logical Operators

In computer language, the expression for meeting multiple criteria simultaneously is called “and” and uses the ampersand & operator. The expression for meeting either one criteria or the other, or both, is called “or” and is denoted using the vertical bar | operator. Finally, the expression for not meeting a criteria is called “not” and is denoted with the exclamation point ! operator.

4.5.3.1 And operator

If you put three or more arguments in your filter() function (the data argument plus two or more criteria arguments), then only rows meeting ALL criteria are kept, so it performs an “and” operation. Thus these two lines of code will return identical results:

4.5.3.2 Or operator

For “or” comparisons, you have to use the vertical bar | operator. For example, this code will return a table with diamonds having a color of D or E.

filter(diamonds, color == "D" | color == "E")#> # A tibble: 16,572 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 55 326 3.95 3.98 2.43

#> 2 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 61 326 3.89 3.84 2.31

#> 3 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 65 327 4.05 4.07 2.31

#> 4 0.22 Fair E VS2 65.1 61 337 3.87 3.78 2.49

#> 5 0.2 Premium E SI2 60.2 62 345 3.79 3.75 2.27

#> 6 0.32 Premium E I1 60.9 58 345 4.38 4.42 2.68

#> # ℹ 16,566 more rowsThis can get a bit cumbersome if you have multiple criteria, but there is a shortcut. You can combine all the values you want to keep using the c() function and then use the “in” operator %in% like this:

4.5.3.3 Not operator

“Not” comparisons can be used to pick rows that do not meet a given criteria. The ! operator generally should be followed by parentheses () with the affirmative criteria inside them. For example, this code will return a table of diamonds with any color except E:

filter(diamonds, !(color == "E"))4.5.3.4 Missing values

Missing values are a story for a later date! You don’t need to know this yet, but if you find yourself here looking for an answer, you can filter values without a “missing value” for color like this:

The diamonds dataset does not contain any missing values, so the results here are uninteresting, but at least now you know how.

4.5.4 String helper functions

There are a variety of other functions you can incorporate into your filter() function to achieve specific results.

For example, if you are dealing with a text column (e.g. character, factor, or ordered), you may wish to filter based on something more precise than simply == or !=. Let’s say you want to find all diamonds with a clarity of VS1, VS2, VVS1, or VVS2. You could use the “or” operator, or the “in” operator. But what if you don’t even know all the possible clarity values and you just want everything that contains "VS" anywhere in the word. There is a string-based helper function str_detect() which looks for a particular string of text inside a text variable:

filter(diamonds, str_detect(clarity, "VS"))#> # A tibble: 29,150 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 65 327 4.05 4.07 2.31

#> 2 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 58 334 4.2 4.23 2.63

#> 3 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 57 336 3.94 3.96 2.48

#> 4 0.24 Very Good I VVS1 62.3 57 336 3.95 3.98 2.47

#> 5 0.22 Fair E VS2 65.1 61 337 3.87 3.78 2.49

#> 6 0.23 Very Good H VS1 59.4 61 338 4 4.05 2.39

#> # ℹ 29,144 more rowsThe function itself is the comparison, there is no operator like == or !=.

The name of the variable you want to look in goes inside the str_detect() function as the first argument, while the text you want to detect is the second argument, surrounded by double quotes.

If you want to pick only values of clarity that start or end with particular text, you can use the functions str_starts() or str_ends(). For example:

filter(diamonds, str_starts(clarity, "VS"))

filter(diamonds, str_ends(clarity, "2"))

4.6 Arrange rows with arrange()

The arrange() function will allow you to sort the rows in a data frame based on the values in one or more columns. It always returns a data frame with the same number of rows as the input data frame.

The first argument is the data frame to sort. Subsequent arguments are the names of columns by which to sort.

For example, to sort the diamonds data frame by cut:

arrange(diamonds, cut)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.22 Fair E VS2 65.1 61 337 3.87 3.78 2.49

#> 2 0.86 Fair E SI2 55.1 69 2757 6.45 6.33 3.52

#> 3 0.96 Fair F SI2 66.3 62 2759 6.27 5.95 4.07

#> 4 0.7 Fair F VS2 64.5 57 2762 5.57 5.53 3.58

#> 5 0.7 Fair F VS2 65.3 55 2762 5.63 5.58 3.66

#> 6 0.91 Fair H SI2 64.4 57 2763 6.11 6.09 3.93

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsYou can see that even within Fair cut diamonds, there is still considerable variation in price. If you want to further sort within each cut, you can add additional arguments:

arrange(diamonds, cut, price)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.22 Fair E VS2 65.1 61 337 3.87 3.78 2.49

#> 2 0.25 Fair E VS1 55.2 64 361 4.21 4.23 2.33

#> 3 0.23 Fair G VVS2 61.4 66 369 3.87 3.91 2.39

#> 4 0.27 Fair E VS1 66.4 58 371 3.99 4.02 2.66

#> 5 0.3 Fair J VS2 64.8 58 416 4.24 4.16 2.72

#> 6 0.3 Fair F SI1 63.1 58 496 4.3 4.22 2.69

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsIf you sort a character (text) variable, it will sort alphabetically. If you sort a factor or ordered variable, it will sort based on the order of the factors levels, which you can see using levels() . For example levels(diamonds$cut) .

4.6.1 Descending order

To sort a variable in descending rather than ascending order, you can wrap the variable name in the desc() function. For example, to sort so that the worst cut diamonds are at the top of the data frame, and within those the highest priced diamonds are at the top, you could use:

#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 10

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2.01 Fair G SI1 70.6 64 18574 7.43 6.64 4.69

#> 2 2.02 Fair H VS2 64.5 57 18565 8 7.95 5.14

#> 3 4.5 Fair J I1 65.8 58 18531 10.2 10.2 6.72

#> 4 2 Fair G VS2 67.6 58 18515 7.65 7.61 5.16

#> 5 2.51 Fair H SI2 64.7 57 18308 8.44 8.5 5.48

#> 6 3.01 Fair I SI2 65.8 56 18242 8.99 8.94 5.9

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsWhy do some Fair cut diamonds cost so much? Probably because they are huge! The first 6 diamonds in that list are all at least 2 carats in weight.

4.7 Select columns with select()

The select() function allows you to select which columns (i.e. variables) to keep, or conversely which ones to remove. The function returns a new data frame with the same number of rows as the input data frame, but with fewer columns as specified by the arguments.

The first argument is the name of the data frame. The subsequent arguments are the names of the variables you want to keep.

For example, say you wanted to focus on the variables carat, cut, and color, you could use:

select(diamonds, carat, cut, color)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 3

#> carat cut color

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E

#> 2 0.21 Premium E

#> 3 0.23 Good E

#> 4 0.29 Premium I

#> 5 0.31 Good J

#> 6 0.24 Very Good J

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsTechnically, you can also select variables by their position, so select(diamonds, carat, cut, color) is equivalent to select(diamonds, 1, 2, 3)

select() can also be used to rearrange the order of columns:

select(diamonds, color, cut, carat)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 3

#> color cut carat

#> <ord> <ord> <dbl>

#> 1 E Ideal 0.23

#> 2 E Premium 0.21

#> 3 E Good 0.23

#> 4 I Premium 0.29

#> 5 J Good 0.31

#> 6 J Very Good 0.24

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsThere is also a shorthand for selecting many variables that appear consecutively in the data frame using the colon : operator. For example, to select every variable from carat to price (which would include carat, cut, color, clarity, depth, table, and price), you could do:

select(diamonds, carat:price)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 7

#> carat cut color clarity depth table price

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 55 326

#> 2 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 61 326

#> 3 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 65 327

#> 4 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 58 334

#> 5 0.31 Good J SI2 63.3 58 335

#> 6 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 57 336

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rows4.7.1 Removing variables

Sometimes its easier to say which variables you don’t want to keep rather than which ones you do. In those scenarios you can put a hyphen (negative symbol) directly before a variable name. The resulting data frame has all the variables except the one you named. For example, to return every row except table, you could do:

select(diamonds, -table)#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 9

#> carat cut color clarity depth price x y z

#> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 326 3.95 3.98 2.43

#> 2 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 326 3.89 3.84 2.31

#> 3 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 327 4.05 4.07 2.31

#> 4 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 334 4.2 4.23 2.63

#> 5 0.31 Good J SI2 63.3 335 4.34 4.35 2.75

#> 6 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 336 3.94 3.96 2.48

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rowsTo remove several variables, you can prepend each one with a -. You can even remove a range of values, but the syntax is quirky. You have to put the - before each variable name. For example, to remove x, y, and z variables:

select(diamonds, -x:-y)4.7.2 Helper functions

Sometime you have to work with a massive data frame that contains dozens or even hundreds of variables. In those cases it can be cumbersome to name every variable to add or remove.

There are several functions that can be used within select() :

starts_with("abc")finds all columns whose name starts with “abc”ends_with("abc")finds all columns whose name ends with “abc”contains("abc")finds all columns whose name contains “abc”everything()finds all columns that have not already been explicitly added or dropped. This is useful if there are a few variables you want to move to the front (left) of the data frame.

For example, the following code would move table and price to the front and leave everything else at the end:

select(diamonds, ends_with("e"), everything())#> # A tibble: 53,940 × 10

#> table price carat cut color clarity depth x y z

#> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 55 326 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 3.95 3.98 2.43

#> 2 61 326 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 3.89 3.84 2.31

#> 3 65 327 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 4.05 4.07 2.31

#> 4 58 334 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 4.2 4.23 2.63

#> 5 58 335 0.31 Good J SI2 63.3 4.34 4.35 2.75

#> 6 57 336 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 3.94 3.96 2.48

#> # ℹ 53,934 more rows4.8 Combine multiple operations

Up to this point, you have learned how to perform one action at a time, either filtering, arranging, or selecting. But what if you want to perform multiple steps in a row?

You have three basic options:

- Create intermediate objects

- Nest functions

- Use the pipe

Let’s use an example to illustrate each option. For this example, let’s say you want to perform the following actions with the diamonds dataset:

- Pick only diamonds with a weight of 2 or more carats

- Sort the diamonds by price

- Select only the variables variables carat, cut, and price

4.8.1 Create intermediate objects

One solution is to do each step one at a time, creating intermediate objects along the way using the assignment operator <-. In our example, this might look something like:

big_diamonds <- filter(diamonds, carat >= 2)

sorted_big_diamonds <- arrange(big_diamonds, price)

select(sorted_big_diamonds, carat, cut, price)One drawback to this approach is that it leaves two intermediate objects cluttering up your environment, neither of which you need. You could either leave them, or remove them using rm().

Another drawback is that there is a lot of code, because the object names have to be long enough so you know what they represent. To solve this problem, you could use shorter names like this:

The code is a lot smaller, but it is less understandable at a glance, and you still have intermediate objects left behind.

You might be tempted to just overwrite the existing diamonds dataset with the new one:

diamonds <- filter(diamonds, carat >= 2)

diamonds <- arrange(diamonds, price)

select(diamonds, carat, cut, price)The issue here is that you no longer have your original diamonds dataset. If you do not mind that, then this is a decent solution. You might use this option if you want to clean up a dataset after reading it from a file, for example to rename unwieldy variables or deal with missing values.

What if you need to use the original diamonds dataset again? Of course, it didn’t disappear, and you can still access it by specifying the package ggplot2::diamonds or by removing diamonds from your global environment rm(diamonds). But overall, this isn’t an ideal solution.

4.8.2 Nest functions

Another option is to nest each function inside the other:

It works, but it is hard to read and interpret at a glance.

4.8.3 Use the pipe

A more elegant solution is to use the special pipe operator |>. Using the pipe, x |> f() is equivalent to f(x). The pipe operator takes what is to the left of the pipe and uses it as the first argument to the function to the right of the pipe.

Using this option, we could do:

The pipe is like saying “take this thing, then do this to it, then do this to it”. Pipes can make your code simpler, shorter, and easier to read.

You can find a more complete discussion in the Pipes chapter in R for Data Science.

4.9 Assignment

Open your penguins-assignment.R script by clicking on the name in the Files tab (or if its already open click its tab in the source pane.

For this assignment you will work with the Palmer Penguins dataset you used in the previous lab.

Check to see if the palmerpenguins package is already installed by selecting the Packages tab in the bottom right pane. In the search field, type “palmer” and you should see the package if it is installed. If it is not, click the Install button and type palmerpenguins to install it.

Begin by loading the tidyverse and palmerpenguins package in your R script:

4.9.1 Questions

Now use what you know from previous labs, and what you have learned from today’s lab, to perform the following data manipulation tasks.

Put a comment like # question 1 on the line before each code chunk, so you (and I) can read your script more easily.

- Print the penguins dataset

- Filter penguins to include only Gentoo penguins

- Filter penguins to include everything except Gentoo penguins

- Filter penguins to include only penguins on Biscoe Island.

- Filter penguins to include only Adelie Penguins on Biscoe Island.

- Filter penguins to include only Chinstrap penguins with bill lengths greater than or equal to 50 mm.

- Filter penguins to include only Chinstrap penguins with bill lengths greater than or equal to 50 mm and flipper lengths less than 196 mm.

- Filter penguins to include only observations with a missing value (

NA) for bill length - Arrange all penguins by body mass

- Arrange all penguins by decreasing flipper length

- Select only the columns species and sex

- Select the column species and all columns that begin with “bill_” using the

starts_with()helper function - Select all columns except those ending with “_mm”

- Extra credit: Use pipes to select female Adelie penguins with a bill depth of at least 18 mm, arrange the results by decreasing bill depth, and select only the columns year and flipper_length_mm, in that order.

4.10 Submission

When you have completed the questions listed above, save your files, commit your changes, and push them to GitHub.

-

Next, you will create a lab report:

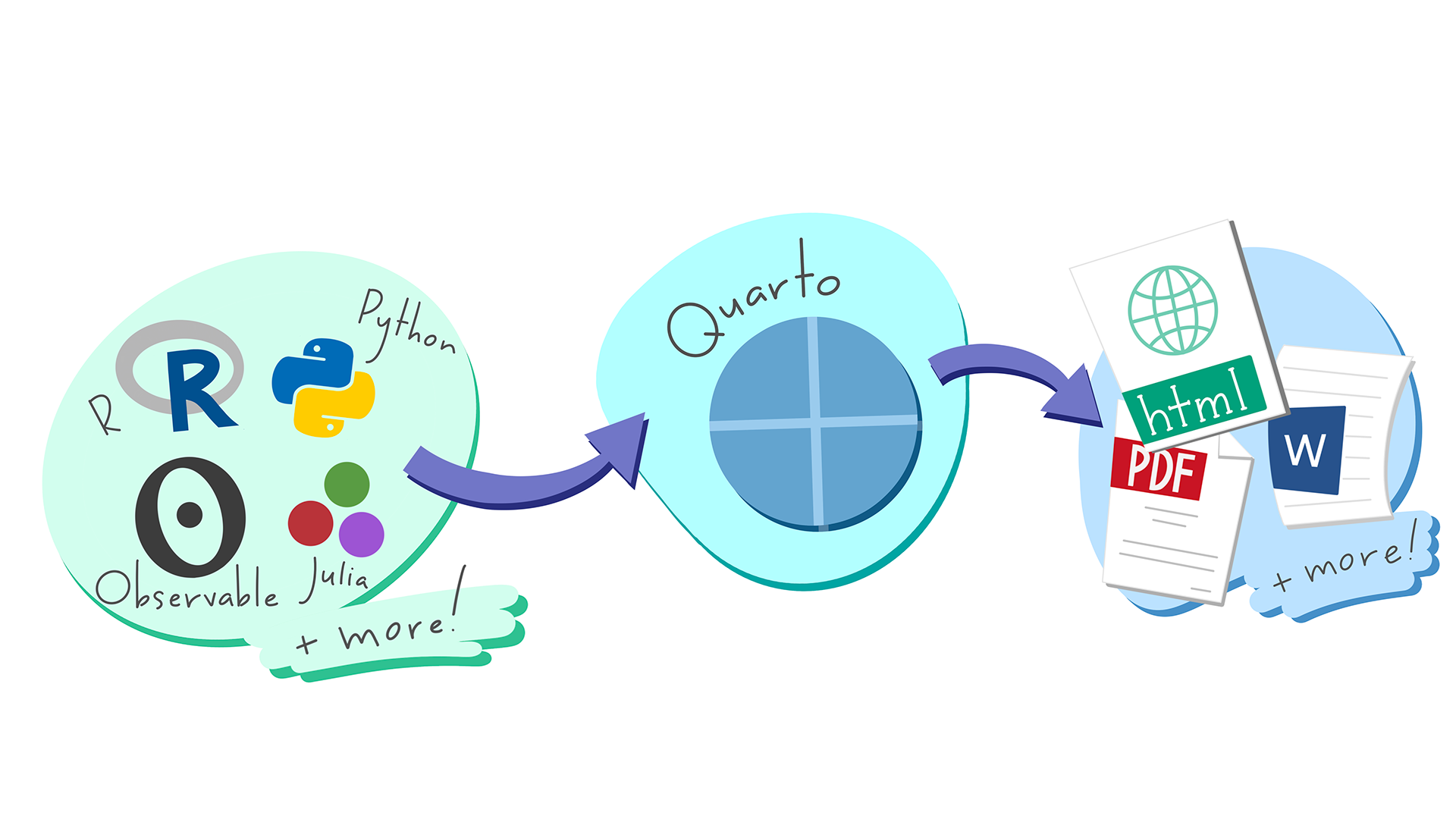

- Create a new Quarto Document by going to File > New File > Quarto Document…

- In the dialog window, click the “Create Empty Document” button

- Save the document as

lab-report.qmd - Replace the YAML header with the YAML header from your Lab 3 script (find it on GitHub, copy it, and paste it here). Edit the title so it says the name of this lab. Be sure the format is github flavored markdown with

format: gfm - Make sure you are in the Visual Mode for the next parts. Click the “Visual” button on the left of the tool bar near the save button.

- Add a code chunk after the YAML and load the tidyverse and palmerpenguins packages in it

- Copy the questions in the Questions section above, then on a new line in your report, paste the questions.

- After each question, create a code chunk and copy and paste your (already working) code from your R script to the report, one output per question. Each question should produce a table output.

- Render your document

Again, save your files, commit your changes, and push them to GitHub.

Copy the URL to your

lab-report.mdfile (not qmd) on GitHub.Submit that to the Assignment on D2L.

4.11 Further reading

Your lab manual, R for Data Science (R4DS), contains detailed instructions on filtering, arranging, and selecting in Chapter 5: Data transformation.

You do not need to read the chapter, but it would certainly help solidify the concepts introduced in this lab.

If you do want to read the chapter and try their examples in your own R Script then don’t forget to install the nycflights13 package as described in R4DS Section 1.4.4 Other Packages.